A Ramadan Renaissance - How Can We Revive the Ramadan of the Golden Age?

There's honestly something magical about Ramadan that stirs the soul.

There’s a serenity in the air. You act different. You think different.

It's like the entire Muslim world takes a deep, collective breath, and has been gasping to dive head-first into a month of introspection, connection, and a good dose of divine inspiration. Yet, amidst the hustle of preparation, a crucial question hangs in the air: will this just be yet another ritualistic routine Ramadan, or a REAL one which is reflective, re-energising and restorative for the soul?

Let’s be honest, for many of us, Ramadan has become synonymous with the ultimate food fest and increasingly overzealous social iftars. Yes, we look forward to it with mouths watering and recipes at the ready. But deep down, we know there’s more to this sacred month than just feasting after fasting.

This all led me down the rabbit hole - just how WAS Ramadan celebrated and practised in the Golden Age of Islam?

Rediscovering the Real Richness of Ramadan

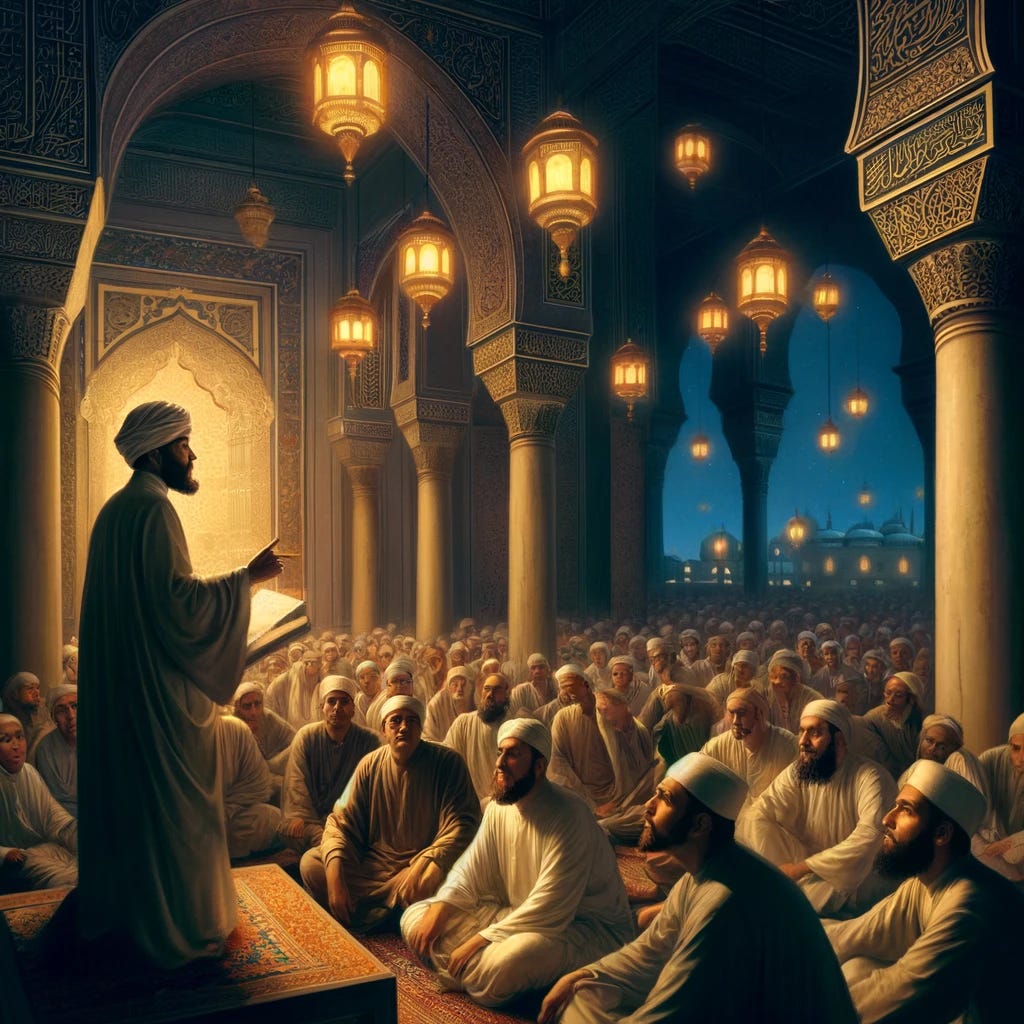

Imagine, for a moment, a Ramadan that echoes the golden eras of our past—a time when the air buzzed with the vibrancy of community, the richness of spiritual and intellectual curiosity, and an overwhelming sense of charity, unity and purpose.

Community

In the Abbasid era (750-1258), the sense of community during Ramadan was palpable.

Streets around mosques buzzed with anticipation as people gathered for suhoor and iftar, reinforcing the bonds of Ummah. The Abbasid caliphs in Baghdad would sponsor grand public iftars every evening. These elaborate meals featured a variety of dishes and ensured everyone, rich or poor, could enjoy a communal Ramadan experience. This tradition of communal meals is a practice that, while still observed in cities like Makkah and Medina, has waned in its universality.

Anecdotes from history tell of the Ottoman Empire (1299-1922), where a cannon fired at sunset not only marked the end of the day's fast in Istanbul but also symbolized the communal breaking of fast across the Empire, a practice that tied the community together with a single, resonant boom. This tradition continued for centuries.

The canon-firing tradition is said to have begun in 1460, when Mamluk Sultan Al-Zaher Seif Al-Din Zenki Khashqodom received a cannon as a gift from a German acquaintance. Testing the cannon, the sultan’s soldiers fired it at sunset, coinciding exactly with the maghreb call to prayer that marks the end of the day’s fast. City inhabitants believed that this was the sultan’s way of alerting them that the time to break the fast had arrived.

Similarly, the Mughal emperors in India would also use cannons to signal the end of the fast each day. This tradition was often accompanied by elaborate firework displays.

In Indonesia, between the 16th and 19th centuries, they would announce the breaking of the fast each evening through traditional drum rhythms, known as "bedug," which became a unique Ramadan tradition.

It’s not just the breaking of the fast - there was also a communal approach to waking up for suhoor. Before there was an alarm clock, there was a masaharati, who sounds out the wakeup call. During Ramadan, a masaharati was tasked with walking the streets to rouse Muslims for suhoor by playing a flute or beating a drum, saying “Wake up, sleeper, there’s no God but Allah the everlasting.” The first masaharati was Utbah bin Ishaq, a 7th-century governor of Egypt. As he walked through the streets of Cairo at night, he called out, “Servants of Allah, have suhoor, for there is blessing in suhoor.”

Across the Islamic world, Ramadan brought a festive atmosphere to marketplaces. Special Ramadan delicacies and foods for iftars would be available, creating a vibrant economic boost for the community. In Indonesia for example, Ramadan saw a surge in the preparation of special dishes like kolak (sweet coconut soup) and onde-onde (sweet rice balls). These delicacies became synonymous with the festive spirit of the holy month and were distributed widely.

Lanterns were also a symbol of Ramadan. Coloured paper ornaments and lanterns called Fanus, also known as Ramadan lamps; adorned all shops, houses, balconies and streets. This tradition, which symbolizes unity and solidarity for Muslim dated back to 969, and often heralded the coming of Ramadan. This tradition has remained in some places, such as Egypt to this day.

Knowledge-Seeking

The nights of Ramadan in the Ayyubid dynasty under leaders like Saladin (1171-1250) were alive with worship and scholarly pursuit, with the leaders setting the example for their subjects personally, spending time in the mosque with the Qu’ran and in prayer. Public storytellers would often share tales and religious narratives during Ramadan evenings. This tradition served as a form of entertainment and religious education, especially before widespread literacy.

In Cordoba, during the Umayyad Caliphate (756-1031), Ramadan was a time when the scholars would lead theological and philosophical discussions and debates during Ramadan nights, in addition to night gatherings for tahajjud in the city’s Grand Mosque. That way, they would make room for deep intellectual exchange as well as spiritual discourse.

In West Africa, in the Songhai Empire (10th-19th centuries), there was also a deep emphasis on knowledge sharing. Ramadan was a time for scholars to gather in mosques and share their knowledge in special Ramadan lectures and debates. Sufi mystics in West Africa would also use Ramadan as an opportunity for intense spiritual retreats. They would engage in additional fasting practices and spend extended periods in prayer and meditation.

Abundant Charity

The Prophet (PBUH) reminded us that the best charity is given in Ramadan.

The Golden Age saw this principle in vibrant action., exemplified through both individual and state-led initiatives.

The Abbasids in Baghdad, for instance, set up public kitchens to feed the poor. During this era, the hospitals would also give free meals and medical care to the needy during Ramadan. The Mughals also set up large public kitchens (langars) throughout their empire, providing free meals for all, regardless of religion or social status.

These charity banquets, or ma’idat al-rahman could be extremely large-scale. Egypt’s first Fatimid ruler, Caliph Al-Moezz, for example, is said to have sponsored Ramadan banquets big enough to feed some 100,000 people.

In the Mamluk Sultanate (1250-1517), Mamluk Sultans would actually engage in charitable competition during Ramadan. Each Sultan would try to outdo the other in providing public meals, building soup kitchens, and distributing food and clothing to the poor.

These acts of generosity underscored the holistic approach to fasting, where the physical act of abstaining from food was complemented by acts of kindness and giving, and reinforced the importance of charity and social responsibility during the holy month.

Having said this, despite the grandeur of their civilization, Muslims in the Golden Age practised a commendable simplicity during Ramadan, especially in their own meals.

This reminds us that the essence of fasting is not in the lavishness of iftar but in the humility and self-discipline it instils, with the focus on the spiritual, rather than the material.

So, what is so different about the Ramadan practised in the Golden Age of Islam and the one practised today?

The biggest change of course is the fact our Ramadan is now decentralised and more individual, due to our current state without a Khalifah. We can no longer operate like the Caliphates and Sultans of the past who played a more central role in Ramadan observances and the unity it would foster across the Ummah.

In the past, knowledge-seeking was a key part of the worship of Ramadan, through special lectures and discussions on religious topics. Rulers were often patrons of learning and participated in these scholarly gatherings. Knowledge-seeking is not quite as prominent a focus perhaps, with more emphasis on spiritual rituals such as tarawih - but the advent of technology and digital media has made knowledge-seeking much more accessible and widespread, with new Ramadan releases eagerly awaited annually from Yaqeen Institute and Zaytuna College, amongst others.

The concept of widespread charity over the month has remained largely intact, but has become an increasingly competitive and aggressive campaign across the entire month, with an onslaught of emails, TV advertisements and direct mail bombarding and competing for our attention. We are not necessarily connected to the cause, we digitally automate our giving and it sadly can all feel very transactional at times.

Here’s How We Can Spark a Ramadan Renaissance

The golden age of Islam wasn’t just golden because of its achievements in science, art, and culture. It was golden because of how Muslims lived Ramadan (and beyond): with open hearts, keen minds, and arms wide open to give.

While the essence of Ramadan remains unchanged, the way we observe it has transformed over the centuries. The sense of community, the focus on scholarship, and the simplicity of life have given way to more individual and family-centric practices.

If we look at the situation objectively, it is evident that we still observe remnants of the traditions of a Golden Age Ramadan today. However, the Ummah has seemingly descended to operating on auto-pilot, merely fulfilling her obligations in terms of fasting and worship. If we realised how transformative this month could be for us individually and collectively, we would do everything in our power to revive the traditions and practices of a Golden Age Ramadan. It was a time of intellectual, spiritual, and communal growth for Muslims across the globe as long as they held onto the traditions.

It was what powered the rest of the year.

For me, the key to a Ramadan renaissance lies in one thing - our relationships.

So much focus in the past was on the collective, whether it was communal iftars, community-wide announcements, unifying experiences, social gatherings to seek knowledge and even the charity was very local and hands-on.

This emphasis on strengthening relationships does something to the soul, the social connection and brotherhood it breeds is the catalyst for unity, strength in numbers and shared impact. This is what we DESPERATELY need as an Ummah. We are far too divided, despite our vast numbers. We need to reconnect the hearts of believers to one another.

Once upon a time, it was the leadership and the Khalifah that would engineer the social element. In the absence of this, what can we do ourselves to make Ramadan more about the shared, communal experiences again? There is a definite benefit in individual worship, but the true spirit of Ramadan is in the power of the many. This is what the true values of Ramadan are.

We can live by this on a micro scale first - do good for a neighbour, serve your community, give to local causes. Attend congregational worship and lectures. Forge the bonds and friendships and have the spirit of unity and relationships in your intention.

At the same time, our minds and hearts should be aspiring and making dua for a time where the macro can eventually take place again, through reviving the Khilafah or even a Second Golden Age of Islam.

This Ramadan, let's commit to an intellectual, spiritual and social revival, not just in how we observe this holy month but in how we live it.

May these last ten days of Ramadan be more than just a series of days; may it be a transformation, a journey back to our spiritual roots, and a leap forward into heartwarming connections, purposeful projects forming and eventually becoming the best versions of ourselves.

Only then, by focusing on restoring our relationships (and beyond that, a dream for a united Khilafah), can we spark a true renaissance of Ramadan, insha’allah.

Maa syaa Allah.. Jazaakumullaah khayran